I was either insightful or lucky when I picked Lieutenant Maurice Dease to be the most important infantry solider in The Angel of Mons: A World War I Legend. My early research and my knowledge of what a novel needs led me to the conclusion that Dease would be a fine choice for a major character.

This was confirmed over the years. In 2014 I was in Mons for commemorative events around the Battle of Mons. The night of the 24th Sarah and I attended a sound and light show that had been funded by the City of Mons and the province of Hainaut ($500,000) that had been shown since August 4, the date war had been declared. The narrative was in French, so I was especially attuned to the few words in English. Surprisingly, the name Dease was one of the few. (Others were Arthur Machen and Phyllis Campbell, who also are characters in the novel. There were no others, except a few major officers.)

A recent article in The Irish News tells the story of Dease again, this time to note a Victoria Cross Paving Stone being unveiled. See it on line or read the article here:

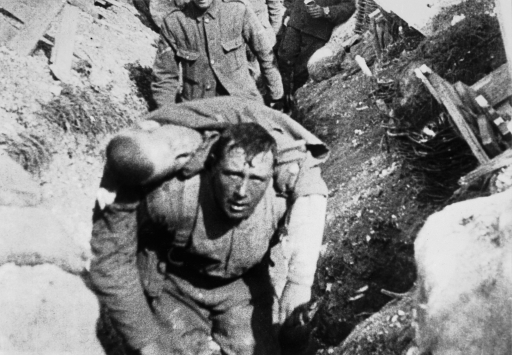

1 BRAVERY: Maurice Dease, who was killed in the Battle of Mons in August 1914

In the late summer of 1914 in Coole, Co Westmeath, the family of Lieutenant Maurice Dease received three telegrams from the British War Office in quick succession.

The first told them Maurice was wounded, the second that he was missing and the third that he was dead.

What the telegrams did not reveal was the extraordinary courage of Maurice Dease that led him to be awarded the first Victoria Cross of the Great War.

Next Tuesday, exactly 102 years after he died at the Battle of Mons, Lt Dease will be remembered in Coole in the country churchyard that stands on a plateau over the Bog of Allen and where his family worshipped for generations.

A Victoria Cross Paving Stone, similar to those in Glasnevin Cemetery, and a small VC cross will be unveiled at an existing cross which was erected by the Dease family after Maurice was killed in 1914.

On August 23, 1914, Maurice Dease was serving with the British Expeditionary Force in Belgium and in charge of a machine-gun section of the 4th battalion of the Royal Fusiliers.

It was the first day of combat and the unit was told to hold a railway bridge over the Mons-Conde Canal at Nimy, outside the town of Mons.

Dease manned a machine gun with a clear line of fire across the canal.

Another gun covered the entrance to the bridge but the British forces were hopelessly outnumbered.

One of the two machine guns jammed. Dease ran through enemy fire to try to fix the gun and was hit in the knee.

He succeeded in fixing the gun and managed to make it back to his post but was hit again in the calf and neck. He continued to man the machine gun until he died.

The citation for his Victoria Cross reads: “Though two or three times badly wounded, he continued to control the fire of his machine guns at Mons on 23rd August until all his men were shot. He died of his wounds.”

Private Sidney Godley, who was wounded and taken prisoner by the Germans, was also awarded a Victoria Cross for his bravery at Mons.

His citation read: “For coolness and gallantry in fighting his machine gun under a hot fire for two hours after he had been wounded at Mons.”

The ceremony on Tuesday has been organised by the Midlands Branch Royal British Legion and the Dease family.

Sunday Independent